The Future, Complexity and The Illusion of Control

09-03-2022 | Interviewer: Leen Paape | Author: Jill Whittaker | Image: Maartje Geels

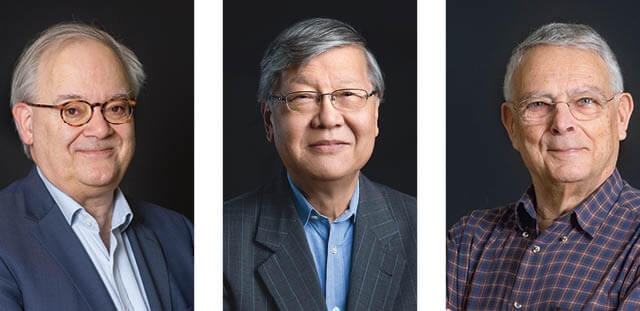

Rising populations have caused global entanglements simply by weight of numbers, types of product and diversity of issues in the past 50 years. Now we face the multiple impacts of the global pandemic, climate change, polarization and growing wealth inequalities. In the face of seemingly uncontrollable shifts, this virtual Round Table addresses how leaders and supervisors should deal with these new complexities. Asking the questions is moderator Leen Paape, Chair of the Nyenrode Corporate Governance Institute and professor of Corporate Governance. Two of the participants are Jan Wouter Vasbinder (Executive Director at Para Limes and former Director of the Complexity Program at Nanyang Technological University) and Peter Robertson (Organization- Ecologist at Para Limes and Visiting Fellow at Nyenrode Business Universiteit). Para Limes is an independent not-to profit organization and platform that focuses on invigorating explorations in a complex world.

Together with Jan Wouter Vasbinder and Peter Robertson, Leen Paape is organizing a three-day conference in May entitled ‘The Illusion of Control’, emphasizing that It is time to think about our future as an emerging context that we do not control. Twelve internationally recognized thinkers have been invited to the conference to share their thoughts on several aspects of this illusion. Topics such as the East-West thinking, complexity and control, neural aspects of illusion and control, complex adaptive management, leadership and engineering, amongst others will be covered. One of the speakers is Andrew Sheng who joins the virtual discussion as guest of honor from Penang, Malaysia. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Asia Global Institute, University of Hong Kong and Chief Adviser to the China Banking Regulatory Commission.

Why should business leaders care about complexity?

Sheng: ‘Complexity has always been with us. The second law of thermodynamics tells us that things just get increasingly complex. Every business leader deals with complexity. Your job is to reduce it to simplicity, to simple messages that your firm, your team is able to execute. So life is actually a mix between the trend to become more complex and the struggle of man to make it simpler. Two years ago, we could not have imagined that a pandemic was going to happen. As a central banker, I certainly could not have imagined that central banks would print 7 trillion dollars in a matter of months.’

How could scenario planning and stress testing fail to anticipate a pandemic?

Sheng: ‘In my experience the trigger for a crisis always occurs in an area not under your charge. You never see it. So regulators test the things they know. But they do not know about the unknown unknown.’

Vasbinder: ‘The problem for CEOs it that they deal with experts who only see a very small part of the whole. When trying to set the course for the future, CEOs need to have a broad view, see the interconnections. They need to take a crude look at the whole (an approach advocated by the late Murray Gell-Mann) so that they know where the specialists fit in. When you see all the connections between the specialists you create a totally different world than the sum of those specialists.’

Sheng: ‘Leaders must learn to use unconventional tools such as explore & adapt models instead of the traditional predict & act models, where we can try to explore scenarios for an unknown future and realize that you have to be paranoid to survive. They must realize you have to be paranoid to survive, to quote Intel leader Andy Grove. Take nothing for granted, because things you thought were normal turn out to be not normal, and things you thought were abnormal suddenly become regular.’

So the world is complex and leaders have to be paranoiac. What should they change?

Sheng: ‘Start by prioritizing the important over the urgent. An example: When the 2008 financial crisis occurred, the central banks said: ‘Banks do not have enough capital, they do not have enough liquidity. So let’s implement Basel III’. They spent 12 years implementing Basel III and billions hiring consultants to do capital and liquidity stress tests. Then the minute the pandemic occurred the central banks printed 7 trillion dollars and immediately suspended Basel III. What does that tell you? Either Basel III was a complete waste of time (which it was not) or there was too much focus on micromanaging the crisis.’

As a Costa Rican Minister of Environment once said: We are building sandcastles on the beach, not aware that the tsunami is coming to hit us. The purpose of the board is not to imagine that there will be a tsunami, it is to remind the chief executive: You may be going after that 1-million-dollar profit but you are losing a hundred million of future profit, or jeopardizing our reputation. That is the difference between the urgent and the important.’

Zoom in or zoom out?

In Leen Paape’s experience, business leaders generally zoom in on what caused a crisis, digging into the details of what happened. He advises them to first zoom out and get a view of the whole. Only then do you find places to intervene that you can do something about.

Vasbinder: ‘There is also merit in actually zooming in on complexity. One trend in complexity now is to model everything. It is called agent-based modelling. What it does is to zoom into details and see if all those details taken together can give you a bigger picture that you cannot see yourself. So zooming out is not the only way. But it is a precondition for managing anything in any part of the world involving more than three people.’

Sheng: ‘When you fly at 30,000 feet or even reach the moon, the Earth can look pretty spectacular. But leaders may find themselves blinded when they zoom in close.

CEOs think they are gathering all the information but they are not understanding the real bias or the flaw. Namely that the blind spot is actually the CEO themself. Because they did not see the “unknown” issue or did not deem it important. When suddenly something rears up from nowhere, they blame everyone but themselves.’

Is this about having the wrong paradigm? Is the mindset of the CEO going to hinder them from asking the right questions?

Sheng: ‘Ultimately everything is the paradigm. Take the issue of climate change. As the book ‘Buying Time’ -- which Jan Wouter edited and many of us contributed to --, makes clear, there is no shortage of resources in the world. We can print all the money we need to deal with all the problems we want. But if leaders are blind to the issue, or are politically captured, there is no incentive for them to do anything. If they impose pain on everybody to sort out the long-term structural issue they will get fired. Or as EC Commissioner Jean-Claude Junker put it: We all know what to do, we do not know how to get re-elected after we have done it.’

Do we need to change selection profiles for CEO’s and board members?

Robertson, author of Always Change a Winning Team believes that it is pertinent to look at the composition and dynamics in detail. ‘It is important to get the right strategic, cybernetical diversity of people. Ensure a mix of people who are more exploratory, exploitative and operational. When you copy that cybernetical dynamic in management teams you improve its chances of operating more with more integrity. I agree absolutely with Andrew, about individual leadership and the need for self-reflection. Which can be solved by feedforward and feedback loops.’

What kind of people, competencies and capabilities are needed?

Speaking as a former member of a number of boards and a former securities regulator in charge of corporate governance, Sheng sees diversity as very important. One possible explanation of why German boards function reasonably well is that they always include somebody from a trade union. And having women on the board prevents some companies from making crazy mistakes. ‘Generally speaking they will bring up issues which another male competing with the CEO will not.’

Would a more diverse board be better at signaling blind spots?

Sheng: ‘Yes, but not all CEOs are actually good listeners. And if the CEO is very dominant, they tend to shut down people who are willing to speak up. People on the board who are known to be such straight shooters that they will bring up issues regardless of personal consequences, are the exception.’

Robertson: ‘Andrew mentioned Germany and their power in leadership. Another reason is that family companies are extremely important in Germany, like in the Netherlands. Family companies are another answer to surviving growth curves because they do not look to their children, they look to their children’s children. Balancing longevity with profit. Which comes back to mindset.’

Sheng: ‘Actually we over glorify CEOs and forget that the succession problem is critical. Not just for CEO succession but for product succession and institutional succession. My best prediction of whether a company will fail is when the father insists that the son or the heir behaves like him. In Asia that generally means no-one under-35 gets a say in key decision-making. When a small team of Internet start-ups come up with a new product, like Ali Baba, the traditional logistics firms and the traditional banks say “there is no way they can challenge me, I am safe” - until they are blown out of the water.’

Coming back to models, what is your perspective on the use of models and Basel III with regard to complexity and how to run the finance world?

Sheng: ‘When we talk about models we always have our Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium model in mind. The model is that our systems will go back to normal. But it forgets that life is not a simple algorithm – it is an interaction of very complex algorithms. And if you do not have the mindset to recognize that, you die by your simplistic model. What if the whole system does not go back to normal and suddenly lurches out into space? Of course lurching out into space is not necessarily all bad. Sometimes it can take to a completely new path which is very exciting for the company or the country or the community as a whole.’

Does the regulatory environment need to understand complexity better than they do?

Sheng: ‘The problem is that the business model of companies is X and the business model of regulators is Y. The Y model is killing the X-model because the whole business of making profit comes from taking risk. The regulators forget that there is a regulation risk that is actually killing the companies.’

So what can CEOs and regulators learn at our conference?

Vasbinder: ‘That the Western emphasis on efficiency and regulation gives only an illusion of control. That they should stop looking for a single cause-and effect-relationship to pin everything on. And that the alternative to our reductionist thinking lies in the study of emergence and patterns. When you consider systems of patterns you don’t look for generalities that are valid everywhere, you seek to balance all the changing patterns at play in an integrated approach. Giving a new lens through which to consider complexity.’

This article was published in Management Scope 03 2022.

This article was last changed on 09-03-2022