‘Insecure women’ as a convenient and dangerous argument

Author: Maartje Laterveer | Image: Ricky Booms | 24-06-2025

Several years ago, I moderated a panel on diversity and inclusion where, among others, Alexander Pechtold participated. The former D66 leader and self-proclaimed feminist said that he is an advocate of more women at the top, but he wanted to add that when he calls a man with an attractive offer, the answer would be ‘why did you not call four years earlier?’ If he calls a woman with the same offer, she responds by asking if she is qualified enough. Neelie Kroes, also on the panel, nodded in agreement. She and everyone in the room knew what Pechtold was referring to: the general insecurity of women in the workplace, which makes them less likely to end up at the top than the average self-confident man. It is an argument that I have heard more often since, and to which, on the face of it, there is little to argue against. Because yes, many women are insecure. And women are still underrepresented at the top. The only question is whether there is a direct causal relationship here.

The self-help industry does not consider this to be a question. The 'confidence gap' is widely accepted as an explanation for gender inequality. An entire industry of books, courses and coaches has developed around it, rigged to help women become stronger in their own right and thus learn to play the game better. But what if this seemingly well-intentioned explanation is actually part of the problem? What if the so-called confidence gap is not a gap, but a trap – a convenient argument for placing responsibility for structural inequality on women, rather than where it belongs: on the organizations and systems that perpetuate it?

A dangerous moment for a seductive narrative

This question is more urgent than ever. We are in a political climate where diversity initiatives are being openly criticized by right-wing conservative politicians who, for now, have the wind in their sails. The discourse around woke culture and reverse discrimination has found mainstream acceptance, even in moderate circles. At the same time, anti-feminist sentiments are quietly being normalized by online influencers reaching young men with content that portrays feminism as the enemy and women as inferior to men. These young men are not lone wolves who fall prey to the dark web in an attic somewhere. They are the up-and-coming talents in the workplace, in our universities, in our organizations. In conversations with women, I hear disturbing stories about young male colleagues who openly doubt the usefulness of gender diversity and fear for their own opportunities ‘now that women are so favoured.’ This climate makes effective diversity policies both more pressing and more difficult.

In this context, the narrative of insecure women becomes even more tempting for organizations. It offers an apparent way out: send talented women to a leadership programme that boosts their confidence and wash your hands of it. The problem is that this solves nothing. It masks systemic problems as individual shortcomings, leaving the status quo intact.

The myth debunked

First, let us look at the facts. The confidence gap argument has often been supported by the statistic that women only apply for jobs at one hundred percent qualification, while men think they can do it as early as sixty percent. However, this widely cited statistic appears to be traced back to an unpublished internal Hewlett Packard document from the 1980s - no peer-reviewed research, no scientific methodology.

More recent large-scale research tells a different story. Studies of more than 10,000 participants show that there is no significant difference in the extent to which men and women apply for jobs in which they do not fully meet the requirements. Moreover, men and women give almost identical reasons for not applying: ‘I did not meet the qualifications and did not want to waste time.’

It is true, however, that women in the workplace report lower self-confidence in the workplace more often than men. Studies show that they are less positive about their career opportunities and that they are more likely to suffer from the notorious impostor syndrome – which means continuing to feel like an impostor, and despite obvious competence, not deserving of success. But there are several caveats to these research findings. Because who says that men are really more confident? Research on emotional intelligence shows that men score significantly lower than women on emotional self-awareness. Could it be that they are simply less aware of feelings of insecurity? In addition, studies show that men are less likely to be promoted or receive a pay raise in the workplace if they exhibit behavior that is considered vulnerable. It is therefore conceivable that men are careful about admitting that they are insecure.

The paradox of self-confident women

Even if women do indeed suffer more from impostor feelings, it is highly questionable whether the responsibility for this lies with them. Is it because they are naturally more insecure, or because they function in environments that routinely make them doubt their competencies? Consider a thought experiment: suppose that all women in the workplace were suddenly super-confident. Would they then get more opportunities? Or a pay raise? That promotion? Would gender inequality be solved?

Of course not. Research consistently shows that while confident women are seen as competent, they are not seen as particularly pleasant. They are perceived as manipulative, aggressive, or a bitch. Self-confidence is a quality that society has labelled as masculine, in the same league as independent, dominant, ambitious. We unconsciously expect women to exhibit so-called feminine qualities that are diametrically opposed to the masculine qualities, i.e. being sweet and social, accommodating, emotional, and focused on cooperation.

The result is that men can exert influence without showing social warmth, while women have to prove that they are still ‘feminine enough’ despite their competence. This double standard illustrates that the problem is not with women who lack self-confidence, but with systems that have different standards for masculine and feminine behaviour.

The limited definition of success

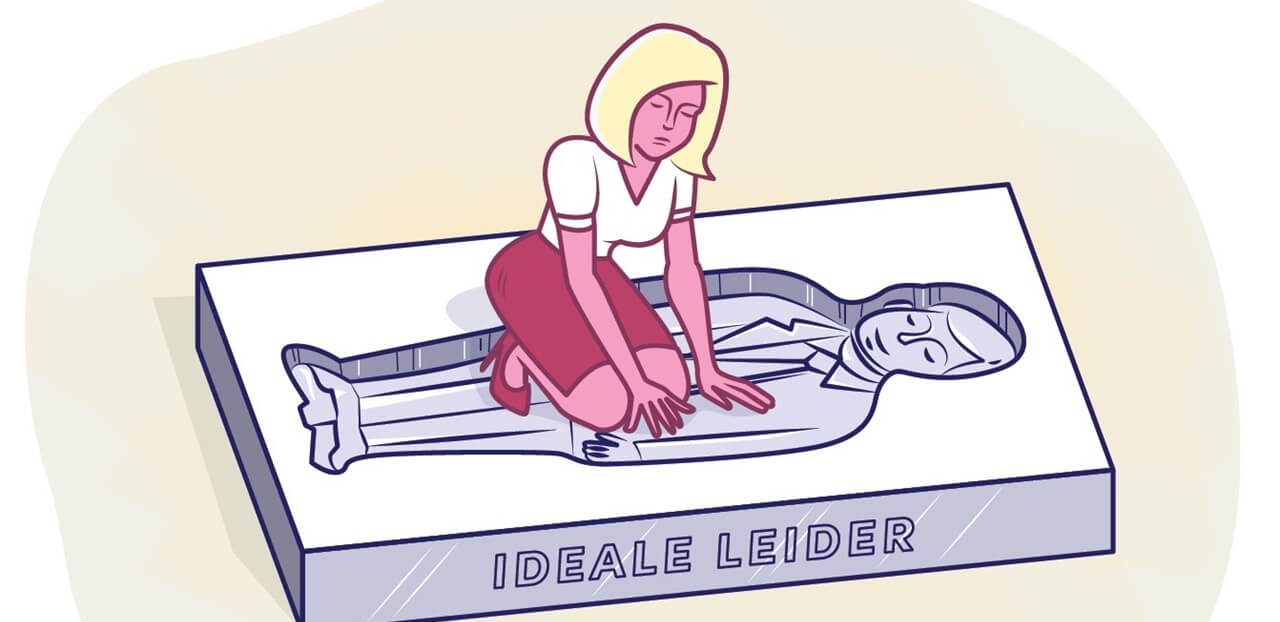

These double standards also point to a more fundamental problem: how we define success. Most organizations are not designed primarily for diversity, but for efficiency and profit maximisation. The type of leader who rises to the top in such a system is the leader who delivers maximum output at minimum cost. This requires employees who are always available, who decide and deliver quickly, who are unhampered by emotions or care commitments, who are decisive and assertive, ambitious, and competitive. These are all so-called masculine characteristics – and when women exhibit these, we know what the consequences are. This definition of ideal leadership excludes not only women, but also men who do not fit this particular archetype. It creates organizations in which a limited set of qualities is valued, at the expense of qualities such as emotional intelligence, collaborative leadership, or long-term thinking. The latter are pre-eminently the qualities needed for an inclusive work environment where diverse talent thrives.

Beyond individual solutions

Self-confidence training can help women feel better but will not fundamentally change their position. The problem is not that women are born insecure – they become insecure through systems that structurally question their competencies and undermine their authority, by cultures that punish them for qualities praised in men.

Real change requires systemic interventions. Transparent criteria for promotions and rewards. Recruitment and evaluation processes that minimize the influence of unconscious biases. Leadership development that creates room for different styles and perspectives. Organizational cultures that recognize and value different forms of talent. Organizations that embrace this holistic approach will not only increase their diversity but also improve their overall performance and innovativeness. This is not idealistic wishful thinking – it is a proven business case.

Real action

The confidence trap is tempting because it offers a simple explanation for a complex problem. But simple explanations rarely lead to effective solutions, they tend to lead to symptom management rather than real change.

Equality is not about fixing women; it is about fixing the systems in which they need to function. We have wasted enough time and resources on diversionary tactics, placing responsibility on individuals while leaving structures untouched. At a time when progress is under pressure, we can no longer afford this. It is time for real action: building systems that enable equality, rather than telling women to change themselves to fit into unequal systems.

Essay by Maartje Laterveer, published in Management Scope 06 2025. Laterveer is an expert on gender, diversity and inclusion and writes regularly on the complexities of modern gender inequality. She has been working as a consultant at &samhoud since March 1, 2025.